Annabelle Tan Kai Lin

A Working Archive of Design, Research and Thoughts

A Working Archive of Design, Research and Thoughts

Handbook of Tropical Metabolism

Supporting the speculative design of a post-tropical eco-corridor, this handbook functions as a pseudo-scientific calculated spreadsheet of materials and resources possible in a self-sufficient ecosystem/ecology. It is collection of local and regional ‘tropical’ ways of life – modern, indigenous and somewhere in between. Semi-scientific, semi-romantic, the handbook broadens our current spaces and flows of material production to a near fictive extreme.

01

Bamboo

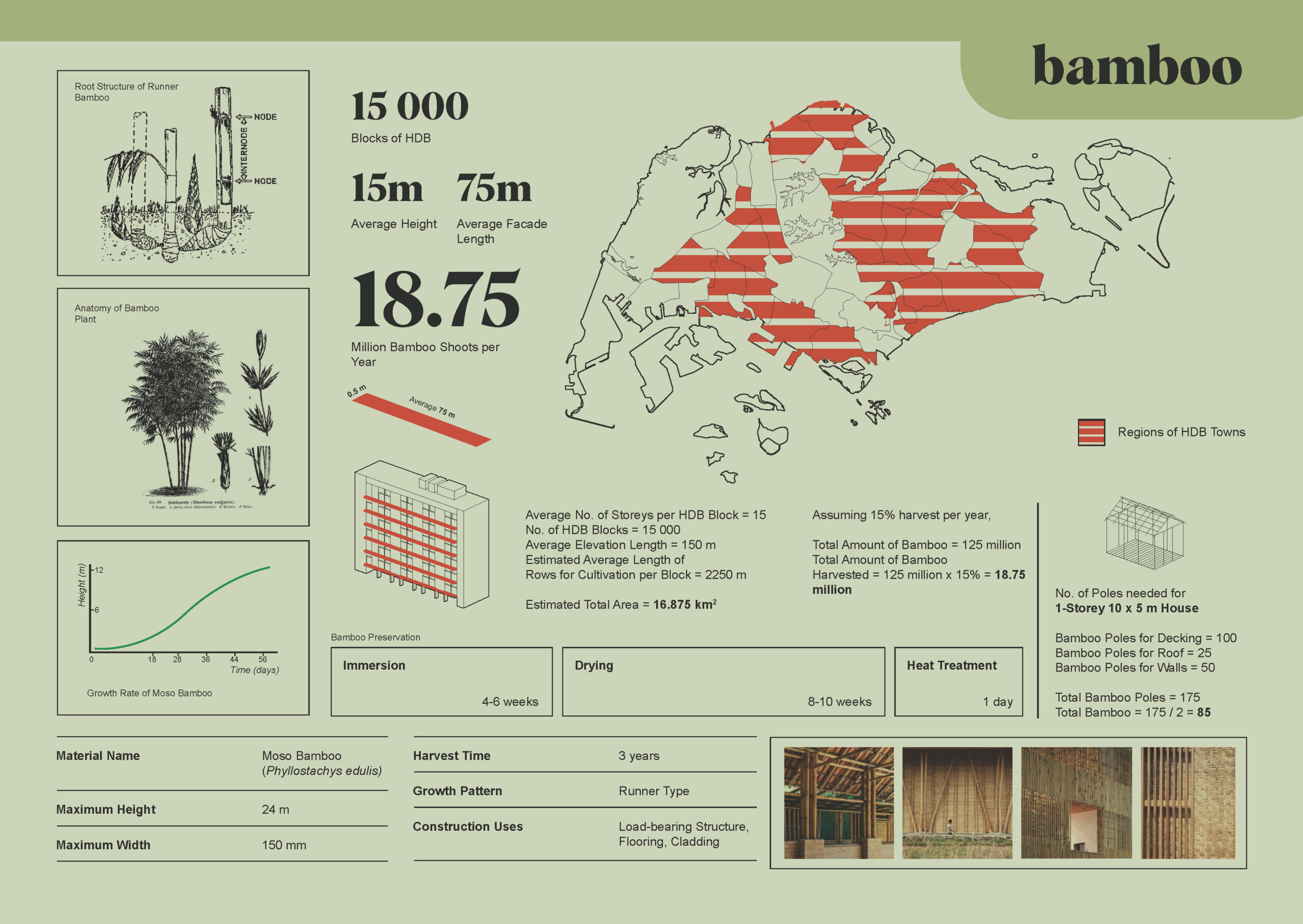

Fast-growing, robust and diverse in its application, bamboo is an obvious, yet sidelined, building material for tropical climates. Bamboo is almost a universal solution for construction, suitable for almost every part of a building system – from load-bearing components to cladding and internal finishes. Being lightweight yet tensile, it has tremendous opportunity to empower collective construction and incremental acts of self-build.

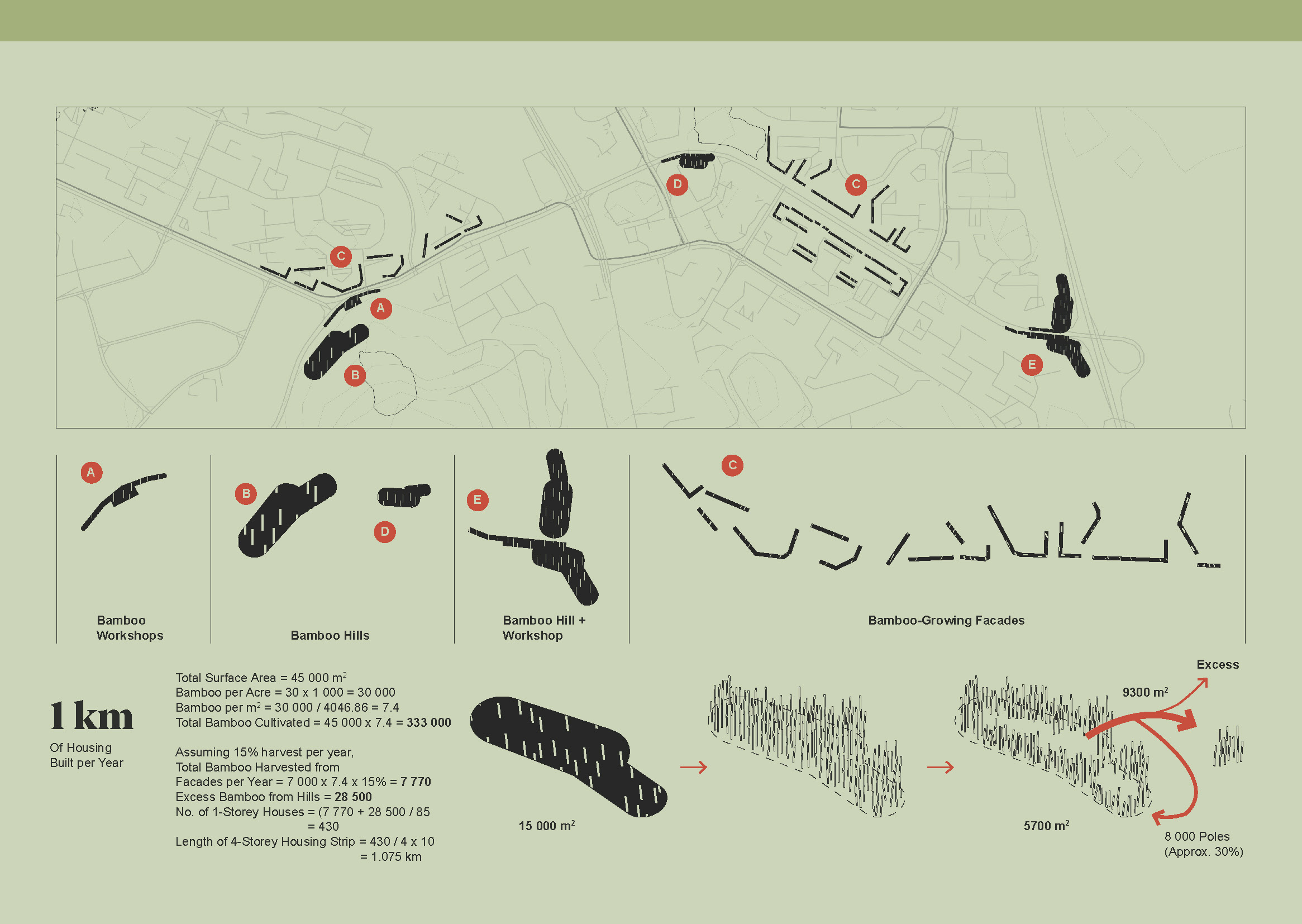

Due to its runner root system, bamboo is able to grow in a linear fashion. The handbook makes use of this characteristic to imagine a growing system that latches onto long modern slab blocks, capture large amounts of solar gain. This maximises vertical area for production, instead of relying solely on horizontal surfaces. Typical housing blocks are mobilised for material production in a radical reimagining of modern infrastructure.

02

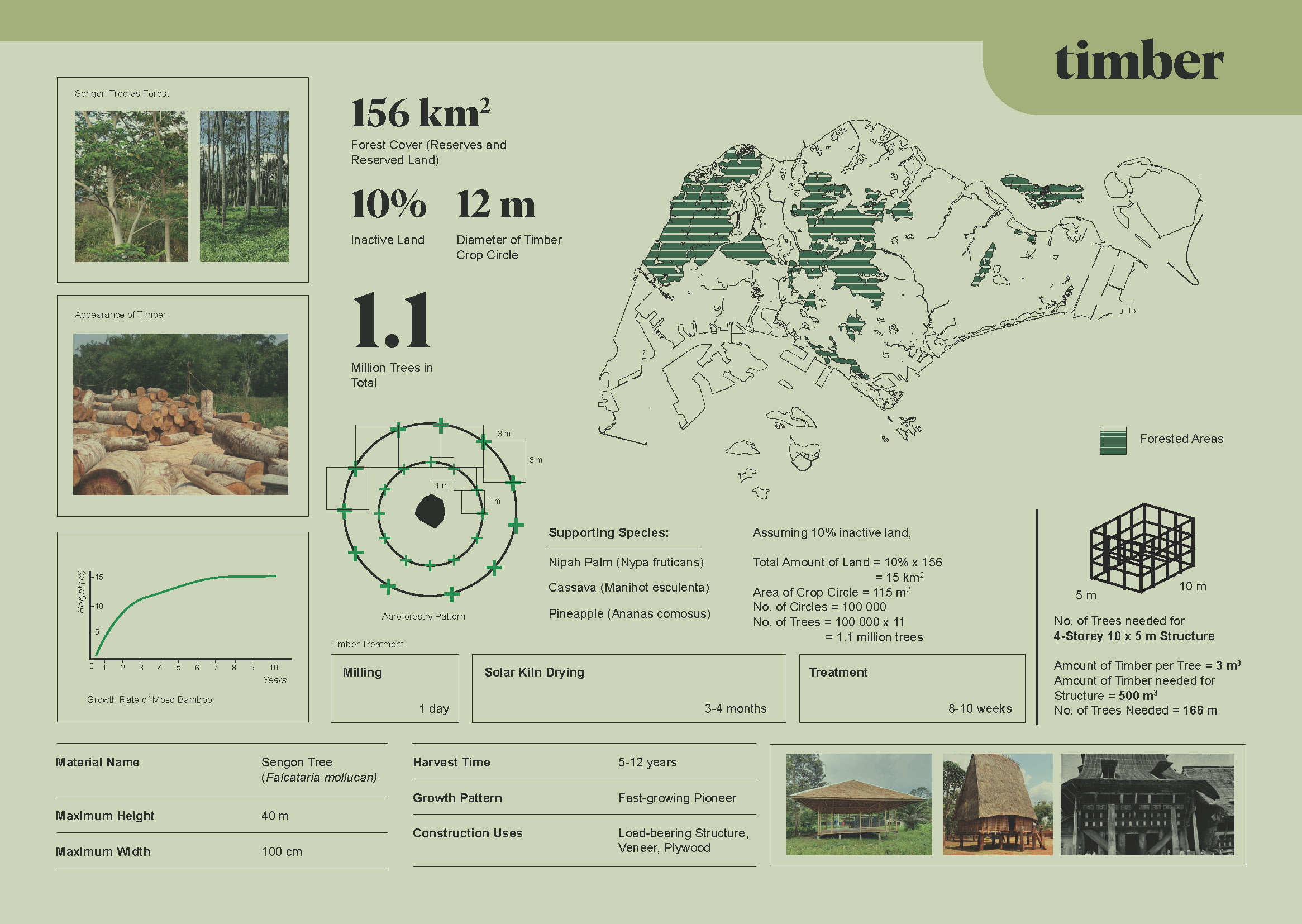

Timber

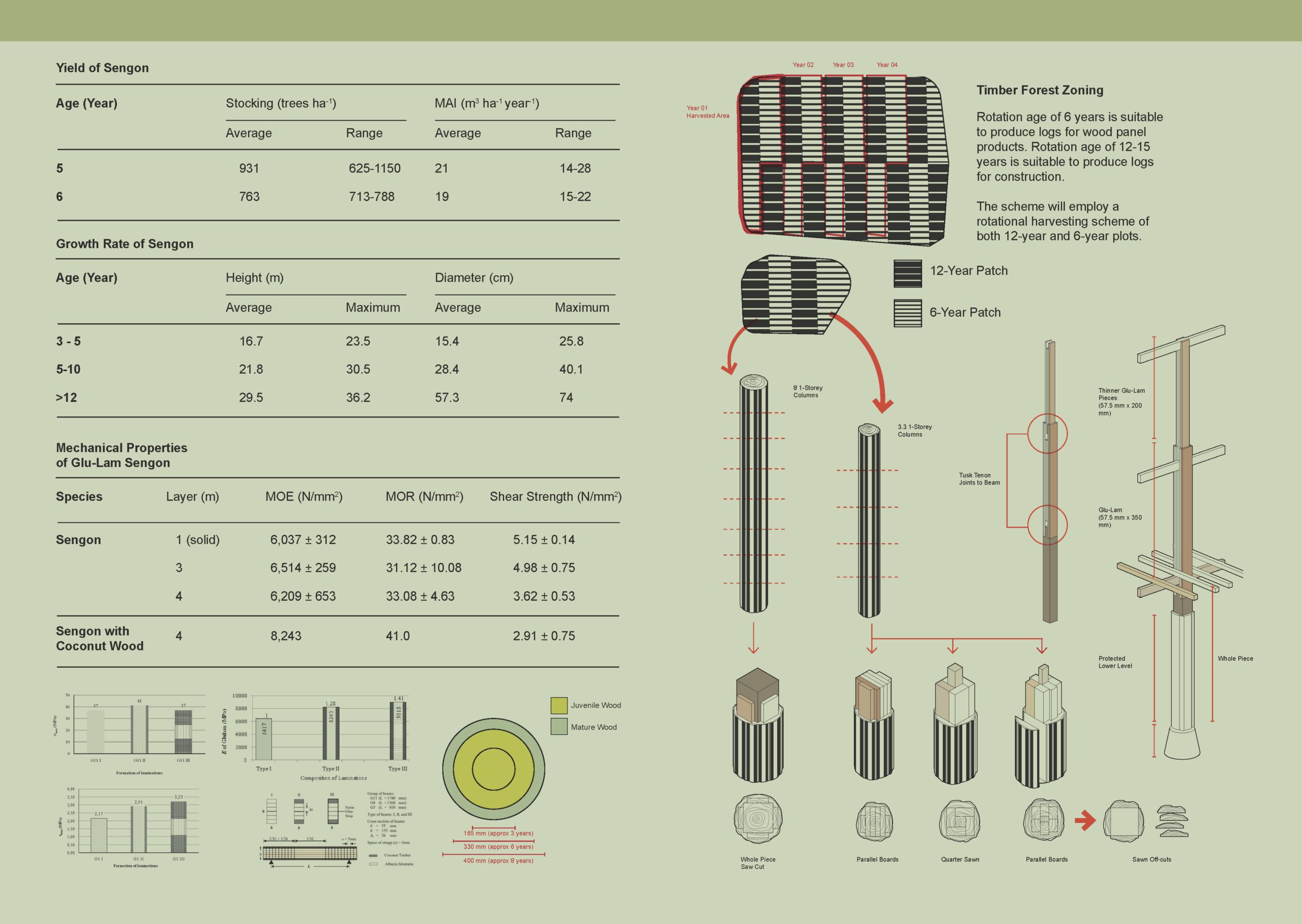

Tropical hardwood and its craft have largely been forgotten in the building industry, relegated to the occasional piece of furniture. As buildings soar higher, there is a fundamental mismatch between building typology and suitable construction materials, leading us to favour unsustainable imported materials like concrete of mass-engineered timber. Yet, tropical timber holds tremendous opportunity for long-term self-sufficiency, when combined with new technology for faster assembly and more efficient material usage.

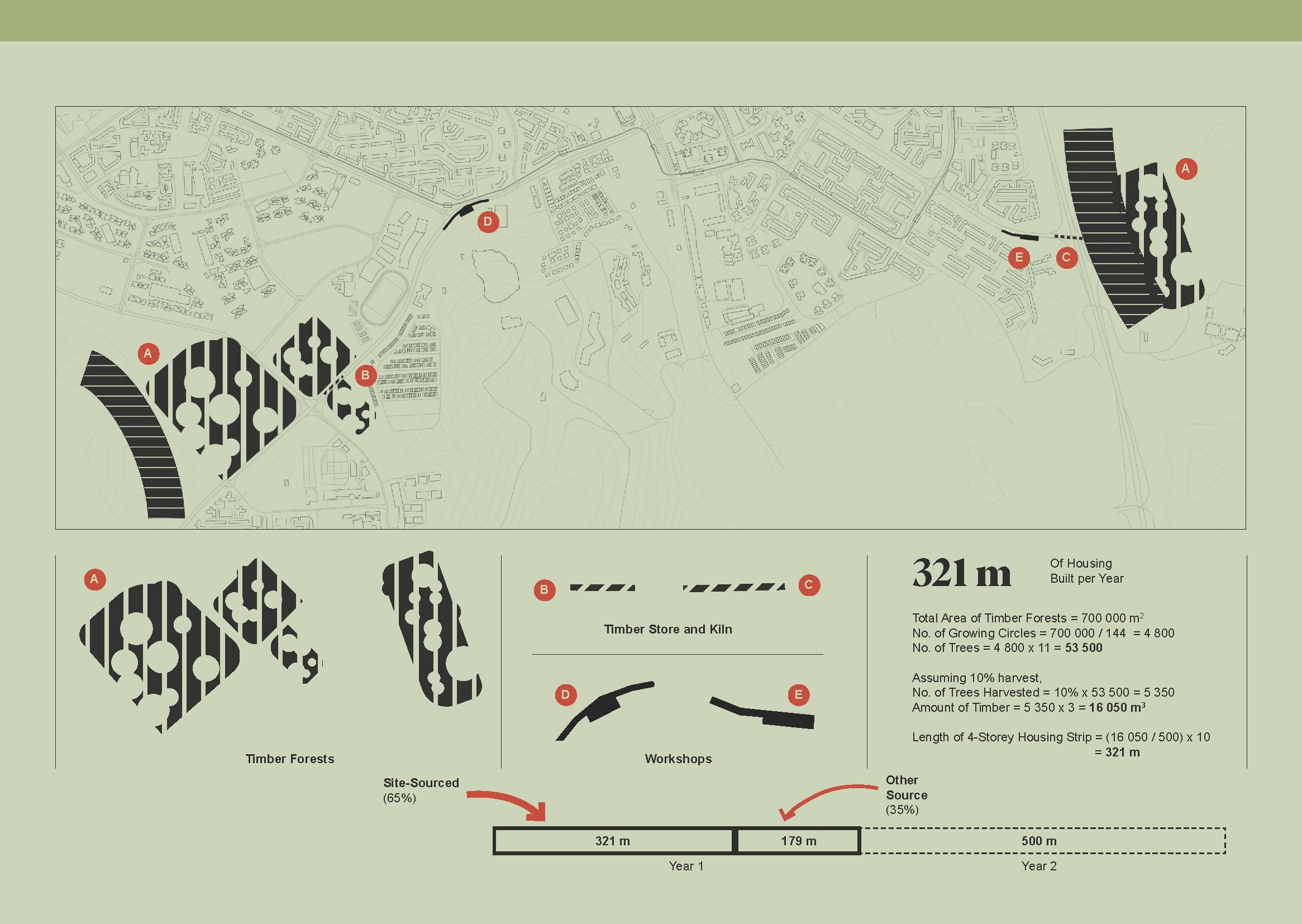

The key to timber is patience. Proposing a rotating timber forest zone, the handbook plots out a swathe of forested land that could yield 6-year and 12-year timber for finishes and structural use respectively. Outside the active harvest area, this forested zone will predominantly remain a lush growing zone, doubling up as a nature park for visitors to learn about forestry. A timber column is designed to make use of the variegated panel sizes derived from wooden logs, tapering in girth as it ascends due to the decreasing building load. This maximises output from our precious 12-year wait for fully grown timber logs, simultaneously crafting a new aesthetic.

03

Brick

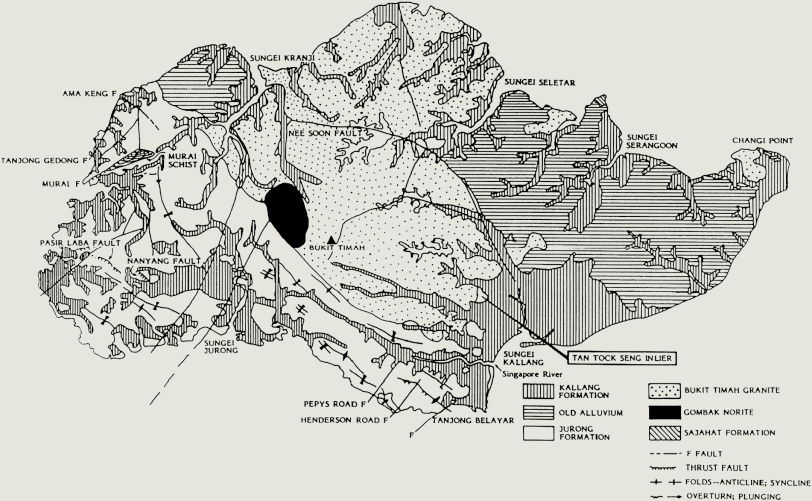

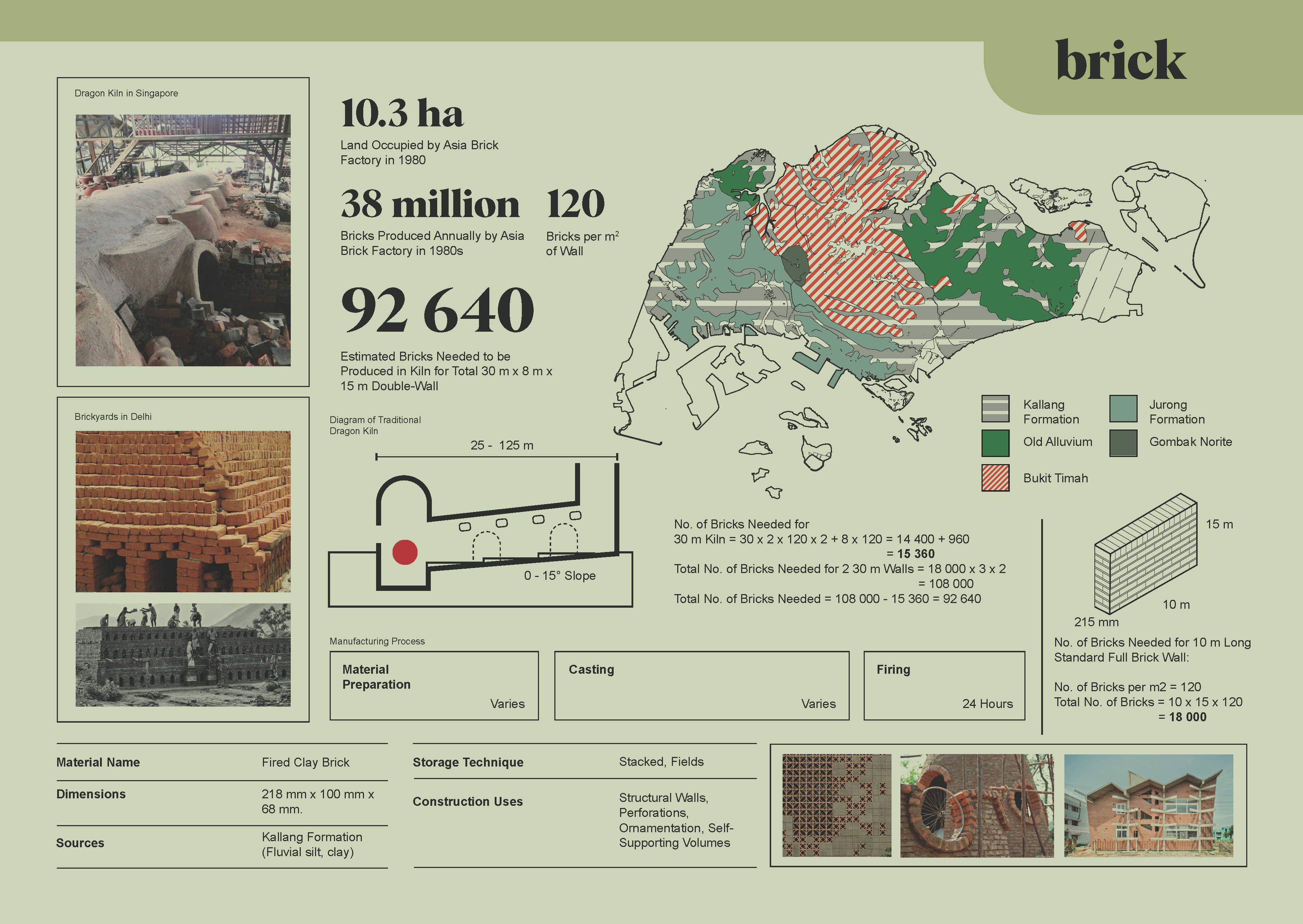

In our recent history, Singapore used to be dotted with brick-manufacturing factories which were critical in supporting our early building industry. Hidden beneath our modern infrastructures of concrete and tarmac, the clay found in the southern and western parts of the island is naturally suitable for brick production.

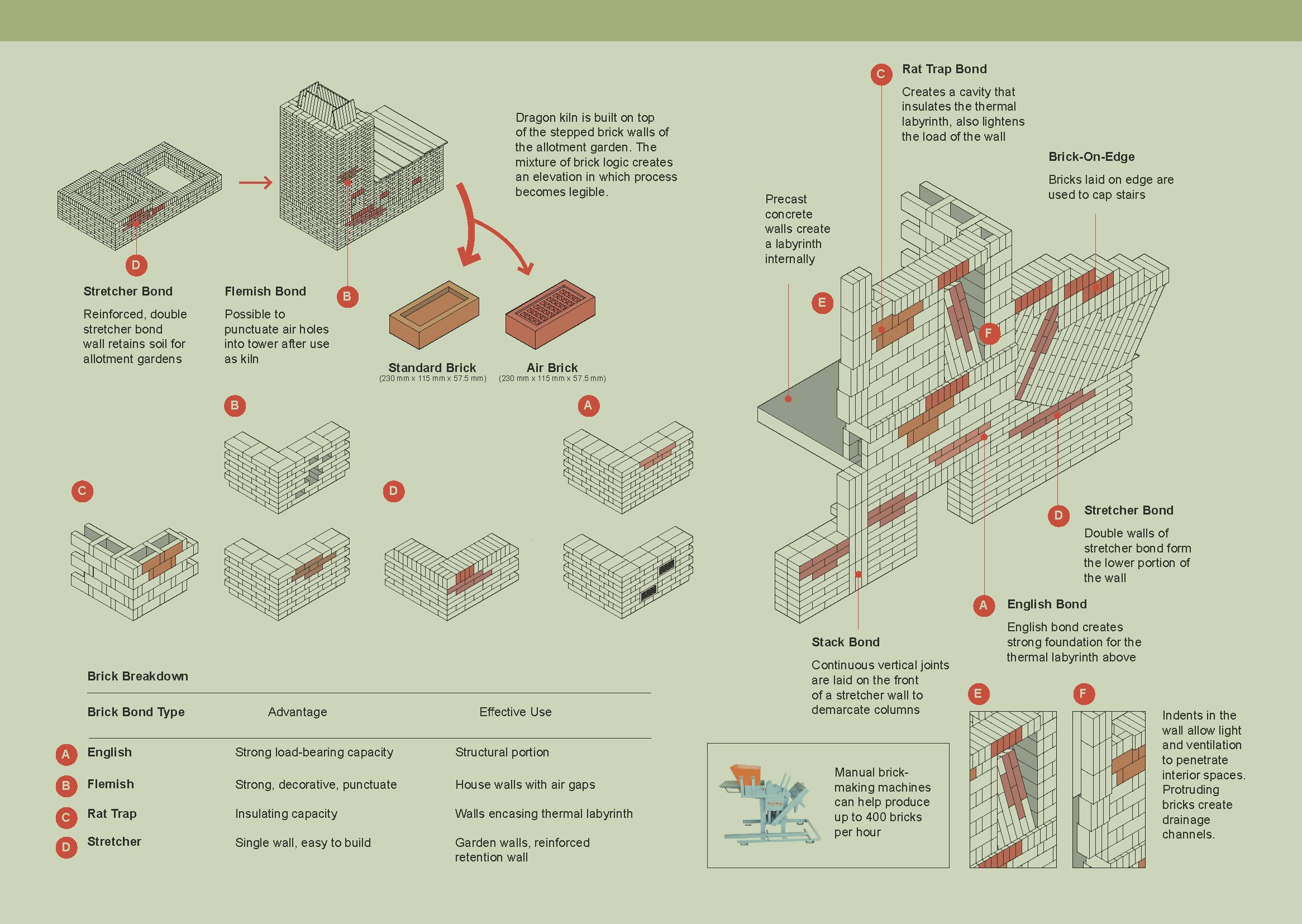

The large amount of land and labour needed for the making, drying and firing of clay bricks eventually led the government to decommission these brick kilns. How can the process and sites of production merge with the the final inhabitable building? Self-supporting brick kilns in India, or even our own surviving dragon kiln – a charming remnant of the brick and pottery industry – are almost an architecture in themselves. Looking to these examples, could a building’s structural system also serve as the kiln that makes itself?